The World Bank has reversed its decade-long stance against financing large hydroelectric dams, approving significant investments in projects like the Rogun Dam in Tajikistan and Inga 3 in the DRC. This shift signals a focus on harnessing hydropower for clean energy, despite environmental concerns and the viability of alternative energy sources such as solar and wind. Critics caution against the social and ecological consequences of mega dams, raising questions about the sustainability of this renewed commitment.

In a significant policy shift, the World Bank has re-engaged in financing large hydroelectric dam projects after a decade of abstention. Historically, the institution was a primary supporter of such infrastructures but moderated its involvement in response to mounting social and environmental concerns. Recently, the bank’s board approved financing for the Rogun Dam in Tajikistan, now a $6.3 billion initiative that promises to be the tallest dam globally. This project, originating in 1976, remains only 30 percent complete and is emblematic of the World Bank’s renewed focus on mega projects.

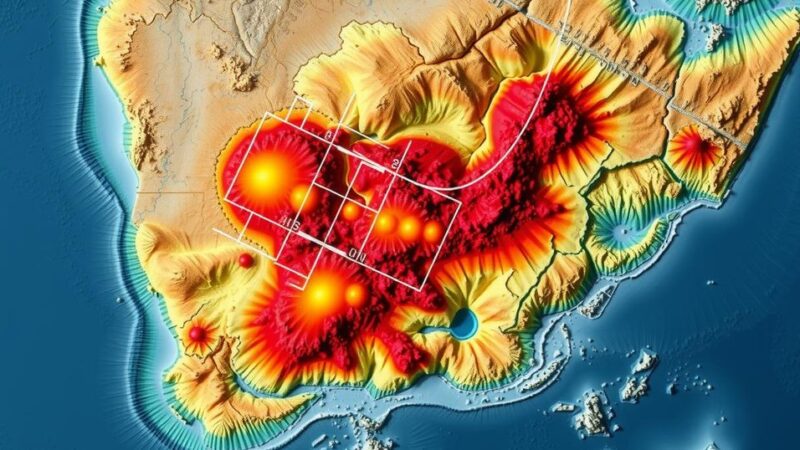

Simultaneously, negotiations are underway for financing Inga 3, part of the expansive Grand Inga Dam scheme in the Democratic Republic of Congo, estimated to cost $100 billion and potentially doubling the power output of China’s Three Gorges Dam. Despite the potential benefits of increased electricity supply, these projects have stirred controversies regarding environmental impacts, displacement of populations, and feasibility amid changing climate conditions.

Additionally, the World Bank’s participation in the Upper Arun Dam project in Nepal signifies its expanded focus on high-cost hydropower advancements. Experts express concern regarding the sustainability of such investments, highlighting the often prohibitive costs associated with dam construction, the lengthy timeframes before generating revenue, and the disruptive effects on local ecosystems and communities. Critics argue that alternative energy sources, such as wind and solar, are increasingly viable and cost-effective, raising questions about the viability of continued hydro investments by the World Bank.

Environmental groups, alarmed by this resurgence in dam financing, have proactively communicated the risks associated with projects like Rogun and Grand Inga. They advocate for a reassessment of these mega dams, citing potential ecological damages and social ramifications. The bank has publicly maintained its commitment to hydropower, framing it as a crucial element of a clean energy investment strategy, nonetheless, the historical context and existing opposition present substantial challenges to these initiatives.

The World Bank, once a staunch advocate for large hydroelectric projects, has exhibited a fluctuating commitment to hydropower development over the past two decades. In response to significant criticism regarding the socio-environmental consequences of large dams, the institution had chosen to limit such investments. However, the recent approvals for the Rogun Dam and Inga 3 suggest a strategic pivot, positioning hydropower as vital for promoting renewable energy in regions with limited access to electricity, despite ongoing debates surrounding the feasibility and ethical implications of mega dam constructions.

The World Bank’s renewed support for large hydroelectric projects, evident in its financing decisions related to the Rogun Dam and Grand Inga, highlights a significant strategic shift that raises numerous concerns. While proponents argue that these projects could yield substantial renewable energy benefits, critics emphasize the myriad of risks, including environmental degradation, community displacement, and long-term sustainability challenges. The ongoing discourse underscores the complexities of balancing energy needs with ecological and social responsibilities, necessitating a critical evaluation of future investments in large hydropower.

Original Source: e360.yale.edu